The alkaline diet for reducing acidity in the body

Western diets with their reliance on processed foods have for some years been seriously disrupting our bodies’ acid-base balance. Find out how you can put this right.

Acid-base balance and food industrialisation

The human body requires a very specific pH level in the blood, in the region of 7.4 (1). This pH is maintained by means of our diet, which is itself influenced by the pH of the environment (land and water).

But intensive farming methods and industrialisation have profoundly affected the pH of our soil and oceans (2). What’s more, the growth of the agro-food industry has exacerbated imbalances, with increases in saturated fats, simple sugars, preservatives and other additives (3).

As a result, our mineral levels suffer as modern Western diets encourage imbalances between potassium and sodium in favour of sodium, and between chloride and bicarbonate, in favour of chloride. These disparities can lead to metabolic acidosis which can be damaging, in particular, for the skeleton. (4)

Note: excess sodium and chloride produce acidity whereas an abundance of potassium, bicarbonate and magnesium induce alkalinity.

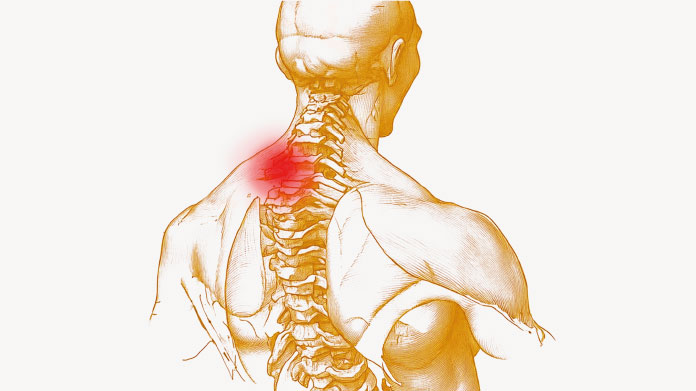

The effects on the body of acid-base imbalance

When the diet is too acidic, the body is forced to restore acid-base balance by drawing on its resources in potassium and calcium, minerals which have an alkalinising effect.

This use of resources to combat the adverse effects of an unbalanced diet can cause demineralisation. Indeed, numerous studies suggest that an over-acidic diet has a negative effect on bone health (5).

In addition, a diet that’s too acidic, especially one high in animal protein not balanced by sufficient alkaline foods, can lead to calcium in the urine, or calciuria (6), a condition that should be avoided at all costs by those who suffer from kidney stones.

There is also scientific evidence that a more alkaline diet is associated with a better muscle mass index in healthy women (7).

The alkaline diet: a natural solution

When food is metabolised by the body, the majority of proteins produce acids, while most fruits and vegetables produce alkalis (8).

To restore the right acid-base balance, it therefore makes sense to prioritise a healthy diet high in fruit and vegetables (the ‘alkaline diet’). All the more so as this doesn’t even take into account the acidity of food in the mouth.

Completely counter-intuitively, it seems that sugary foods are actually acidifying for the body, while many acidic-tasting foods are actually basifying or alkalinising. Refined sugar, for example, is one of the main culprits in causing acid-base imbalances, while lemons are among the most alkalinising foods!

The PRAL index: a helpful tool

The acronym PRAL stands for Potential Renal Acid Load. The higher the PRAL index (above 0), the more acid the food, and the lower, the more alkaline. (9)

Examples: beef has a PRAL of +13.2 (an acid effect), whereas radishes have a PRAL of -3.7 (alkaline effect).

This index has enabled scientists to categorise foods according to their potential acidifying effect on the body.

The most acidic and alkaline foods

Thus the most acidic foods are:

- alcohol, soft drinks and refined sugar (with a pH of around 3) ;

- dairy products, coffee, red meat, pastries and processed foods (with a pH of around 4).

Those with a pH of between 5 and 8 include a number of non-processed foods:

- rice, beetroot, poultry, potatoes and fruit juices (pH of around 5) ;

- fish, coconuts, milk, eggs, pulses (pH of around 6) ;

- tap water and vegetable oils (pH of around 7) ;

- corn, bananas, apples and peppers (pH of around 8).

And the most alkaline foods are:

- salad leaves, avocados, kiwi fruit, celery, and aubergines, as well as papaya and ginger (with a pH of around 9) which you can find in our supplement Alkaline Formula;

- spirulina, broccoli, carrots, lemons, artichokes, radishes, asparagus and raisins (pH of around 10).

Because eating a balanced diet is not about eliminating foods that are too acidic, with the exception of those known to be bad for our health (alcohol, bakery products, processed foods, ready-meals, etc). It is instead about achieving an acid-base balance.

Note: as indicated, tap water normally has a neutral pH, depending on where you live. In some regions, the water is slightly more acidic, and in others, slightly more alkaline (with a pH, in some cases, of up to 8.4).

Some actual examples of an alkaline diet

There’s nothing to say you can’t enjoy a barbecue with friends, even if the barbecued meat (particularly beef) is quite acidifying. Just try and compensate for this acidity by eating a good amount of broccoli or other vegetables at the same meal, making sure you limit the quantity of grains. And why not, for example, offer raisins as an appetiser, or for dessert, with a fruit salad?

You can also choose to take dietary supplements based on alkaline foods such as ginger (with Super Gingerols), spirulina (with Spirulina) or a combination of alkalinising foods (with the comprehensive formulation Alkaline Formula).

Similarly, you could opt for an alkaline water, such as our product Super Water. This not only provides your body with hydration but it has a significantly higher-than-normal pH to help counteract the effects of consuming acidic foods and drinks.

So you now have all the information you need to correct your body’s acidity and restore your acid-base balance.

References

- LEONG-ŠKORNIČKOVÁ, J. A. N. A., ŠÍDA, OTAKAR, WIJESUNDARA, Siril, et al. On the identity of turmeric: the typification of Curcuma longa L.(Zingiberaceae). Botanical Journal of the Linnean Society, 2008, vol. 157, no 1, p. 37-46.

- GOEL, Ajay, KUNNUMAKKARA, Ajaikumar B., et AGGARWAL, Bharat B. Curcumin as “Curecumin”: from kitchen to clinic. Biochemical pharmacology, 2008, vol. 75, no 4, p. 787-809.

- AKRAM, Muhammad, SHAHAB-UDDIN, Ahmed A., USMANGHANI, K. H. A. N., et al. Curcuma longa and curcumin: a review article. Rom J Biol Plant Biol, 2010, vol. 55, no 2, p. 65-70.

- HE, Yan, YUE, Yuan, ZHENG, Xi, et al. Curcumin, inflammation, and chronic diseases: how are they linked?. Molecules, 2015, vol. 20, no 5, p. 9183-9213.

- https://www.has-sante.fr/jcms/c_2911396/fr/helicobacter-pylori-recherche-et-traitement

- JAYAPRAKASHA, Guddadarangavvanahally Krishanareddy, RAO, L. Jaganmohan, et SAKARIAH, Kunnumpurath K. Antioxidant activities of curcumin, demethoxycurcumin and bisdemethoxycurcumin. Food chemistry, 2006, vol. 98, no 4, p. 720-724.

- JAGETIA, Ganesh Chandra et AGGARWAL, Bharat B. “Spicing up” of the immune system by curcumin. Journal of clinical immunology, 2007, vol. 27, no 1, p. 19-35.

- CONCETTA SCUTO, Maria, MANCUSO, Cesare, TOMASELLO, Barbara, et al. Curcumin, hormesis and the nervous system. Nutrients, 2019, vol. 11, no 10, p. 2417.

- RIVERA‐ESPINOZA, Yadira et MURIEL, Pablo. Pharmacological actions of curcumin in liver diseases or damage. Liver International, 2009, vol. 29, no 10, p. 1457-1466.

- PANAHI, Yunes, KIANPOUR, Parisa, MOHTASHAMI, Reza, et al. Curcumin lowers serum lipids and uric acid in subjects with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: a randomized controlled trial. Journal of cardiovascular pharmacology, 2016, vol. 68, no 3, p. 223-229.

- LIANG, Zhaofeng, WU, Rui, XIE, Wei, et al. Curcumin reverses tobacco smoke‑induced epithelial‑mesenchymal transition by suppressing the MAPK pathway in the lungs of mice. Molecular Medicine Reports, 2018, vol. 17, no 1, p. 2019-2025.

- AWASTHI, Himani, TOTA, Santoshkumar, HANIF, Kashif, et al. Protective effect of curcumin against intracerebral streptozotocin induced impairment in memory and cerebral blood flow. Life sciences, 2010, vol. 86, no 3-4, p. 87-94.

- THANGAPAZHAM, Rajesh L., SHARMA, Anuj, et MAHESHWARI, Radha K. Beneficial role of curcumin in skin diseases. In : The molecular targets and therapeutic uses of curcumin in health and disease. Springer, Boston, MA, 2007. p. 343-357.

- SCHIBORR, Christina, KOCHER, Alexa, BEHNAM, Dariush, et al. The oral bioavailability of curcumin from micronized powder and liquid micelles is significantly increased in healthy humans and differs between sexes. Molecular nutrition & food research, 2014, vol. 58, no 3, p. 516-527.

- ANAND, Preetha, KUNNUMAKKARA, Ajaikumar B., NEWMAN, Robert A., et al. Bioavailability of curcumin: problems and promises. Molecular pharmaceutics, 2007, vol. 4, no 6, p. 807-818.

Keywords

178 Days

EXCELENTE TODO

EXCELENTE EN SERVICIO Y PRODUCTOS LOS RECOMIENDO¡¡ GRACIAS¡¡

ANTONIO ARRIAGA

178 Days

EXCELENTE TODO

EXCELENTE EN SERVICIO Y PRODUCTOS LOS RECOMIENDO¡¡ GRACIAS¡¡

ANTONIO ARRIAGA

178 Days

EXCELENTE TODO

EXCELENTE EN SERVICIO Y PRODUCTOS LOS RECOMIENDO¡¡ GRACIAS¡¡

ANTONIO ARRIAGA

373 Days

Productos de excelente calidad!

Productos de excelente calidad!

CRUZ Francisco

373 Days

Productos de excelente calidad!

Productos de excelente calidad!

CRUZ Francisco

373 Days

Productos de excelente calidad!

Productos de excelente calidad!

CRUZ Francisco

462 Days

Suplementos de calidad

Me encantan los probioticos de esta empresa empeze a leer el libro "el revolucionario mundo de los probioticos" Esta empresa tiene todos los probioticos que este libro menciona en ningun lugar los eh podido encontrar solo en Super Smart Los resultados que hemos obtenido en nuestra salud con los probioticos que solo se encuentran en esta empresa an sido sorprendentes. Muy muy agradecida con Super Smart . Si tuvira mil estrellas se las daría.

Cliente

462 Days

Suplementos de calidad

Me encantan los probioticos de esta empresa empeze a leer el libro "el revolucionario mundo de los probioticos" Esta empresa tiene todos los probioticos que este libro menciona en ningun lugar los eh podido encontrar solo en Super Smart Los resultados que hemos obtenido en nuestra salud con los probioticos que solo se encuentran en esta empresa an sido sorprendentes. Muy muy agradecida con Super Smart . Si tuvira mil estrellas se las daría.

Cliente

462 Days

Suplementos de calidad

Me encantan los probioticos de esta empresa empeze a leer el libro "el revolucionario mundo de los probioticos" Esta empresa tiene todos los probioticos que este libro menciona en ningun lugar los eh podido encontrar solo en Super Smart Los resultados que hemos obtenido en nuestra salud con los probioticos que solo se encuentran en esta empresa an sido sorprendentes. Muy muy agradecida con Super Smart . Si tuvira mil estrellas se las daría.

Cliente

488 Days

High quality vitamins!

High quality vitamins!

François-Xavier Yang-Ting

582 Days

Siempre muy conforme

Siempre muy conforme

VINAS Marta Noemi

582 Days

Siempre muy conforme

Siempre muy conforme

VINAS Marta Noemi

582 Days

Siempre muy conforme

Siempre muy conforme

VINAS Marta Noemi

914 Days

Productos excelentes

Productos excelentes Entrega a tiempo

VINAS Marta Noemi

914 Days

Productos excelentes

Productos excelentes Entrega a tiempo

VINAS Marta Noemi